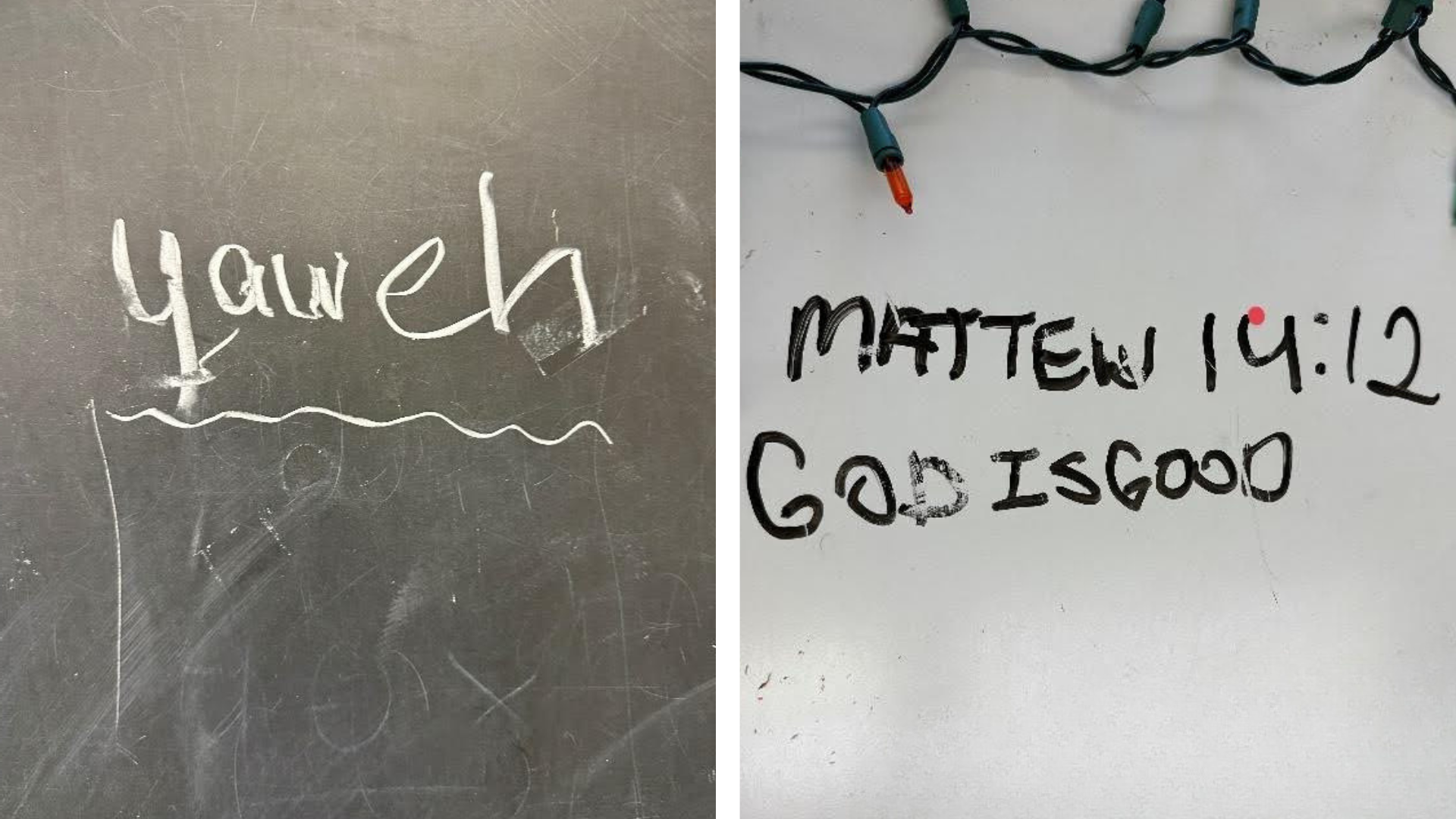

Spelled phonetically and carefully underscored with an undulating white chalk line: yaweh. Strategically placed by the anonymous penman amongst decades of permanent signatures, a place was made for God, in the classroom. I stood for several minutes, attempting to absorb every drop of the spirit that the message contained. My colleagues and I mused about the penman’s identity, noting the heaviness of the chalk and the meticulously scribed letters. We did not erase the message.

A few days later, I placed my hurriedly packed lunch bag on a whiteboard table top that I constructed for students to work out math problems. I was greeted with another spiritual pick me up; “MATTEW 14:12 GOD IS GOOD,” My colleagues and I again discussed the message, this time delivered in dry erase marker by the anonymous penman. We compared the handwriting, and recalled those students who had recently lingered for extra conversation on their way to classes. We pooled anecdotal information on our students’ religious affiliation and local congregations. Yet another space was made for God in the classroom. We did not erase the message. Instead, I wrote my response in dry erase marker; “I’m listening.”

When I began the ICJS Teachers Fellowship, I was determined to create a multireligious space for students where our diverse population could access a calm, quiet space intended for spiritual refuge. As my colleagues and I dialogued this topic at length in one of the very first meetings, my crystal-clear image of how I would contribute to my school’s culture and climate became very murky.

An opportunity arose to teach an art history course in the evening credit recovery program at our alternative accelerated diploma program high school. I hoped to increase my diverse student body’s capacity for religious literacy by embedding the history of world religions into the art history course. Applying the knowledge and understanding of the legal frameworks that exist within the public-school setting combined with my passion for art history helped me meet the gargantuan challenge of building a curriculum and teaching materials with only about 45 days of lead time.

Beginning with rudimentary concepts such as the timeline, and its implicit dualities, allowed me to establish an implicit safe space for students to express themselves and share dialogue. Providing open-ended questions (on the very first day of class—with no context), such as “What is something ancient that you are interested in that we could google and place on this timeline?” yielded answers such as, “I want to know when the Bible was written” and “What years were the life of Jesus Christ?”

Even though my plan was to expose my students to world religions from all continents, they chose to begin their journey with their most familiar reference, Christianity. We organically segued into other religions and belief systems by honoring their experiences and point of view, an ICJS dialogue cornerstone. The prehistoric era, rich with factual evidence of ancient religions and worship offered an objective framework for our evolving dialogue. Students made correlations between the artwork and religious practices, relics, and artifacts with confidence, making brave inquiries of one another. As we continue learning about the heritage and history of each continent, my hope is that students are able to make a personal spiritual connection to the art history content and bravely share it with other students in the classroom.

Vanessa Proetto teaches at Achievement Academy High School, and she was a 2023-2024 ICJS Teachers Fellow. Learn more about the ICJS programs for teachers here.

Vanessa Proetto teaches at Achievement Academy High School, and she was a 2023-2024 ICJS Teachers Fellow. Learn more about the ICJS programs for teachers here.

Opinions expressed in blog posts by the ICJS Teacher Fellows are solely the author’s. ICJS welcomes a diversity of opinions and perspectives.